[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” hundred_percent_height=”no” hundred_percent_height_scroll=”no” hundred_percent_height_center_content=”yes” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” status=”published” publish_date=”” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” enable_mobile=”no” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=””][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ spacing=”” center_content=”no” link=”” target=”_self” min_height=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_image_id=”” background_position=”left top” background_repeat=”no-repeat” hover_type=”none” border_size=”0″ border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=”” last=”no”][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=””]

I sat and held his warm yet lifeless hand in mine. The harsh, liquid-like, rattle of his breathing echoed off the pale yellow walls of the living room. I didn’t want to look at him, but I couldn’t look away. This man, who once seemed larger than life, lay before me almost unrecognizable. Yellowish in color, his skin seemed to hang from his body like a boy wearing his father’s sportscoat.

My older brother Patrick, always quick with a one-liner, sat still and stoic at the head of dad’s hospital bed which had been set up in his ex-wife’s, my ex-stepmother’s home. Anthony, my younger brother, sat to his left across from me. At his feet, Laurie, his youngest and only daughter slowly rocked back and forth in her chair, trying to comprehend what was about to happen.

Around us, pictures clung to the walls like painful reminders of happier times. The now dated floral curtains hung in the windows, partially blocking the bright sunlight and cast long shadows across the well-worn floors.

My father had refused to go back to his own house, a place he lived in the years after the divorce. He also refused hospice. He said he wanted to be surrounded by his family in his house as he still called it. The house he built with his own two hands, now transformed into his final resting place. What made everything worse was not knowing what he was experiencing—he had lost his ability to communicate 24-hours earlier. It was impossible to know if he was in pain, if he was afraid, or if he was even cognizant we were there at all.

“Dad,” I whispered, leaning in, “it’s ok. You raised tough kids. If you are ready, you can go.”

I couldn’t believe what I was saying. It felt as if I was trapped in a nightmare, unable to wake myself.

“Get up,” I wanted to scream.

“You can’t do this. I’m not ready for you to go!”

Instead, I kept calm and spoke softly, hoping my words would bring him some semblance of peace. This was, in truth, my worst childhood nightmare come to life. While most kids worried about what lurked under their beds as they slept or what sat in wait in the darkest corners of their room, my fear was far greater—and real; that my father would die.

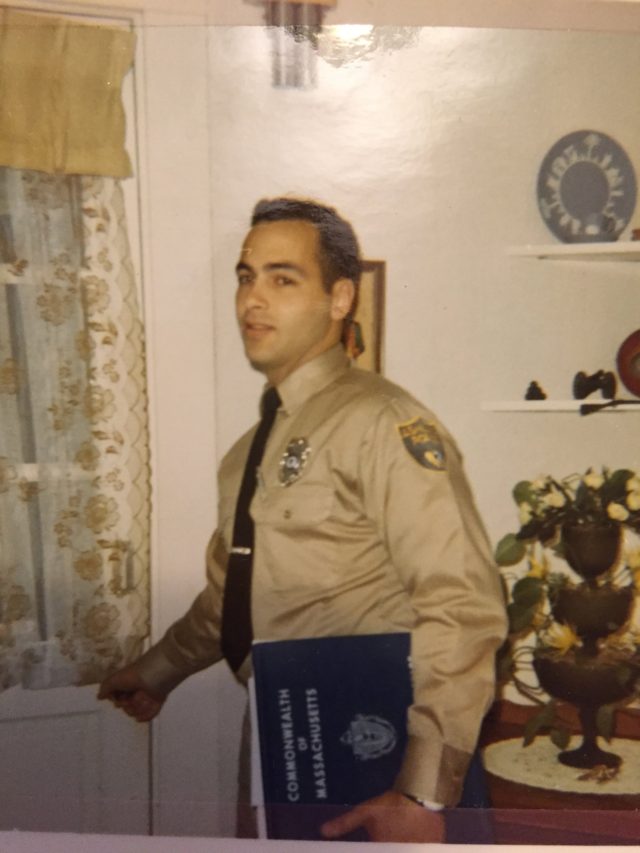

Unlike me, my father always knew what he wanted to do with his life— to be a police officer. That dream became a reality on July 28, 1969, when he was appointed to the Ashland Police Department in the town he grew up in, Ashland, Massachusetts. He loved the thrill of the job. He loved helping people. And he loved being part of the community in which he grew up and lived. To everyone else, he was Officer Zanella, but to me, he was the coolest and toughest guy in the world. After all, he carried a gun, had a badge, and drove around in a police car all day protecting people. He was like a real-life superhero. But unlike Superman, he was not indestructible. And even as a small child, I knew it.

Unlike me, my father always knew what he wanted to do with his life— to be a police officer. That dream became a reality on July 28, 1969, when he was appointed to the Ashland Police Department in the town he grew up in, Ashland, Massachusetts. He loved the thrill of the job. He loved helping people. And he loved being part of the community in which he grew up and lived. To everyone else, he was Officer Zanella, but to me, he was the coolest and toughest guy in the world. After all, he carried a gun, had a badge, and drove around in a police car all day protecting people. He was like a real-life superhero. But unlike Superman, he was not indestructible. And even as a small child, I knew it.

Unless you are the child of a police officer, it’s hard to fully understand what life for me was like. I heard what people would say about the police—both good and bad. I also knew that there were dangers associated with the job. Even at a very young age, I understood there was a real possibility that one night my father could leave for work and never come home. And no matter how many times he told me, “Don’t worry, Stevie. Everything’s going to be ok,” there was no way he could guarantee that.

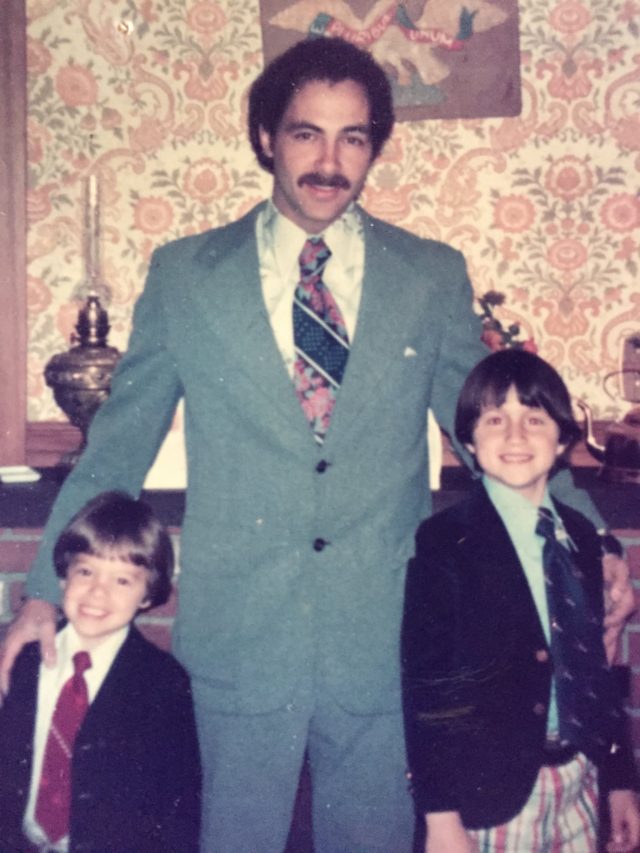

What compounded the issue was that my parents had separated before I was even big enough to see over the steering wheel of my father’s cruiser when he would let me sit on his lap and pretend to drive. This meant I only saw my father every other weekend. I didn’t have that daily reassurance every morning of coming downstairs and seeing him sitting at the kitchen table. I had to go weeks without seeing him before our weekend of pizza, mini-golf, staying up late, and very little discipline reassured me he was okay.

Weekends at dad’s were play-time—when he wasn’t working. His take was he only got limited time with Patrick and me, so he was going to enjoy it. He and our mother did not get along. She resented him for being seen as the fun parent while she was the bad guy. Today, I understand this quite well, but I didn’t understand it then. All I saw was, my parents hated each other and fought all the time. Every Saturday morning pick up was the same—yelling and fighting until we got in his truck and left. And every Sunday night drop off was also the same, but for a very different reason. He would drive us back to our mother’s house, often in silence. Once there I would completely break down into a sobbing mess, clinging to his leg and begging him not to leave.

“Please, daddy. Don’t go!” I would wail over and over, attempting to guilt him into staying.

“But, I have to go,” he protested.

“No. Please don’t leave. I don’t want you to leave anymore.”

My mother would eventually separate us, pulling me into the house where I’d quickly break free from her grasp and escape upstairs. Through the small window in the bathroom, which overlooked the driveway, I’d watch as his headlights faded into the distance as I cried the tears of a little boy saying goodbye to his father for what felt like the final time. The pain and sadness I felt each time was real and left a lasting impression.

My mother would eventually separate us, pulling me into the house where I’d quickly break free from her grasp and escape upstairs. Through the small window in the bathroom, which overlooked the driveway, I’d watch as his headlights faded into the distance as I cried the tears of a little boy saying goodbye to his father for what felt like the final time. The pain and sadness I felt each time was real and left a lasting impression.

You don’t have to be a police officer, or even the son of one, to know that the job is very stressful. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reports that more police die by suicide than in the line of duty and that officers report much higher rates of PTSD, depression, burnout, and other anxiety-related issues than compared to the general population.

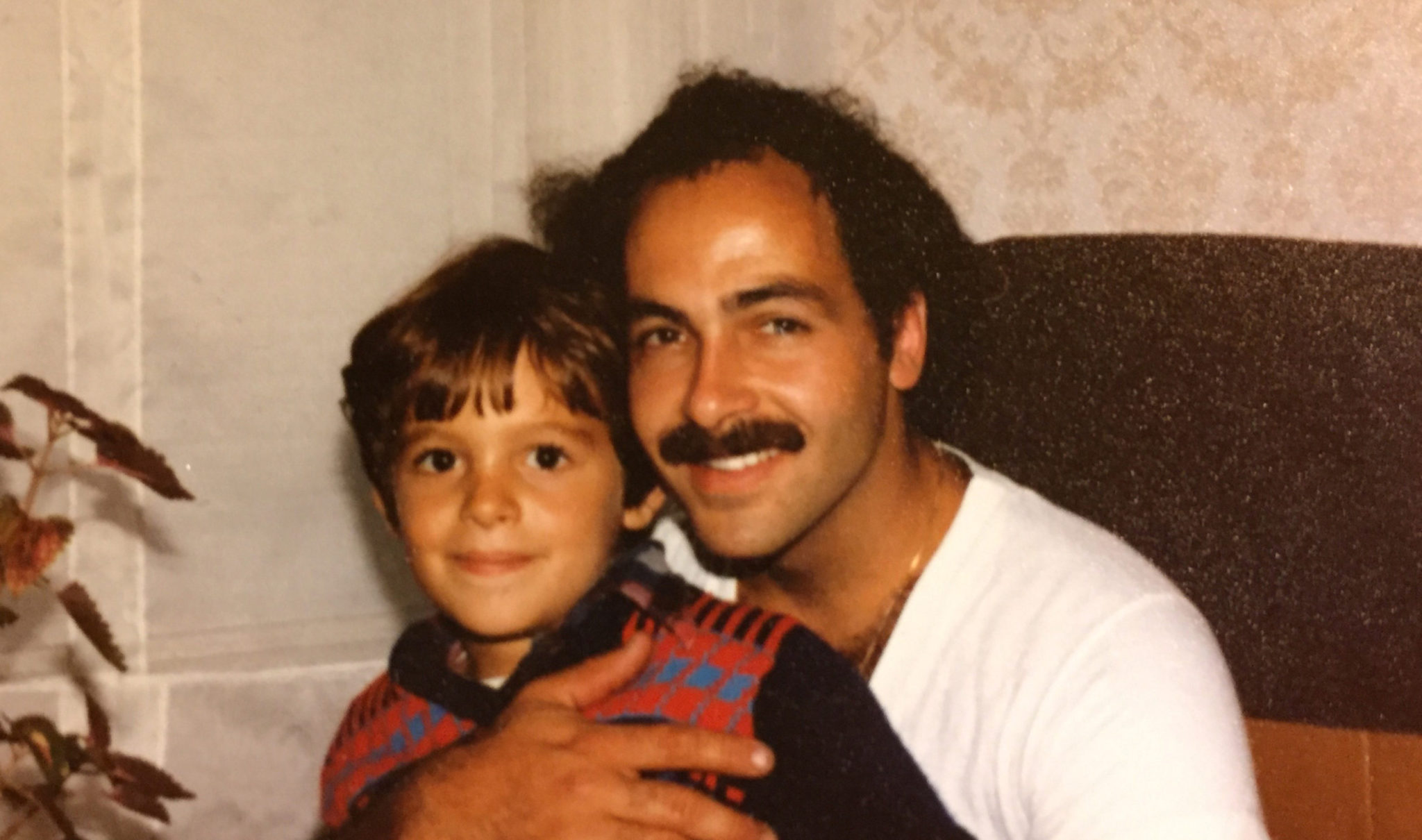

And while my father always put forth a strong image and brave face, he struggled with his own demons. He was a man’s man who loved hunting, fishing, and action movies. He had a mustache like Tom Selleck, a laugh like Burt Reynolds, and biceps like Sylvester Stallone, which he never hesitated to flex just to make us giggle.

He could be funny and silly—patient and kind. He could also be short-tempered, distant, and emotionally unavailable. He looked at the world in a very black-and-white sort of way, believing there was an absolute right and wrong way of doing things. He didn’t like to be questioned and always wanted to be in control. He dealt with the stress of the job by lifting weights and staying active. He also had less healthy coping mechanisms. He started drinking more as he got older. I don’t recall him having a noticeable problem when I was a child, but in later years I began to notice his drinking increased.

He also had a bad reputation for being unfaithful to his wives—first my mother and then my stepmother. I hated him for that. I was embarrassed by his actions and disappointed in his dishonesty. The more I learned about his behavior the more conflicted I felt about looking up to my dad. We never really talked much about it, but once, in a moment of pure honesty, he opened up to me about his behavior.

“Steven,” he said, “let me explain it like this.”

“Yeah,” I said.

“The thing is… I’m like a dog on your front porch. If you chain me up, I’ll chew off my leg to get away. But if you let me roam, I’ll always return home,” he said.

This statement was both eye-opening and crushing. My father didn’t always make good choices. But, nevertheless, I loved him.

That’s the thing about loving someone. It doesn’t always make sense. Sometimes the connections we have with people, especially with our children, defy logic. My father wasn’t always a great father or even a great person, but he was always my dad. And even as our relationship went back and forth over the years between being really close and not speaking, I always had an image of him as my dad. The larger-than-life guy who taught me to catch a baseball in the dusty back yard behind the rundown apartment he rented after my parents divorced. He taught me to ride a bike down the same street he learned to ride in front of the house he grew up in, where his parents, my grandparents, still lived happily together.

He was the one who always made me feel safe and secure when I was by his side. And the man I still desired approval from, even well after I became a father myself.

Much of our relationship in later years centered around my own children and being a dad. I could tell he was proud of who I had become and he loved seeing his grandchildren. He offered me advice on when to be tough and when to let things slide. And he was there for me when I went through my own divorce. Yes, sometimes no matter how hard you try, you still end up like your parents. Even with all my effort to avoid making the same mistakes as my parents, I still ended up in a marriage that didn’t last and two children I was now dropping off on Sunday nights. “Oh, Stevie,” I can still hear him say, “what can you do?”

As I went through my own ups-and-downs—got divorced, found love again, got married, and had my third child—I began seeing the world not just through the lens of a parent, but through the lens of my own parents. I stopped seeing my father as someone who should have known better, but rather as a twenty-something kid with a wife and two kids just trying to his best with what he had. He wasn’t a superhero. He didn’t have all the answers. He was just a guy trying to figure things out—just like me.

We all make mistakes in life. But for some reason, we assume our parents know something we don’t, as if they had some secret handbook for being adults that we will eventually inherit. But what I’ve learned is this: what we actually inherit is perspective—and with that perspective comes the realization that our parents are just people, and people make mistakes.

And while I would always love my father despite all his missteps and misgivings, I would have to work on learning how to forgive him for his mistakes while also learning to become accepting of my own. Because, no matter how hard I try to be a great dad and person, my own children may someday look at me the way I looked at him; with both love and judgment. But forgiveness takes time. And time is the one thing you always think you have more of—until you run out.

I received a phone call one Saturday morning that changed everything. It was my ex-stepmother calling to tell me my father was in the hospital. He had been having stomach pains and couldn’t keep food down. What we originally thought was just a bad stomach bug turned out to be much worse—cirrhosis of the liver.

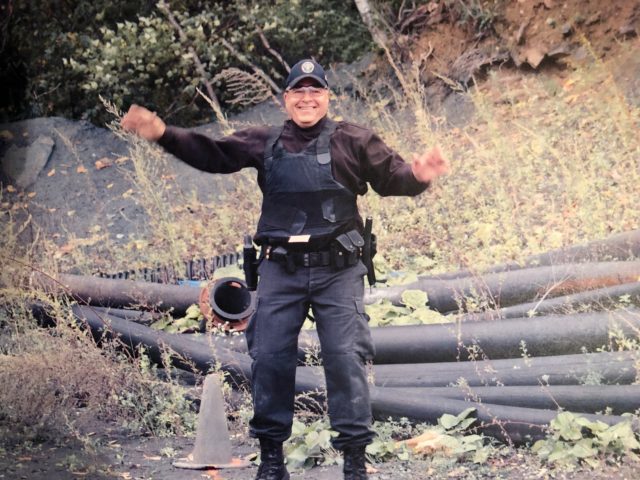

He was four years removed from leaving the police force and couldn’t adjust to being retired. He used to say, “Retired is just another word for unemployed.” His entire identity was wrapped up in being a police officer. It was who he was. When that was taken away from him—by two bad shoulders and a hip replacement—he became lost. He filled his spare time with odd jobs and alcohol. All the years of stress, bad diet, and drinking away the pain had finally caught up to him.

He was four years removed from leaving the police force and couldn’t adjust to being retired. He used to say, “Retired is just another word for unemployed.” His entire identity was wrapped up in being a police officer. It was who he was. When that was taken away from him—by two bad shoulders and a hip replacement—he became lost. He filled his spare time with odd jobs and alcohol. All the years of stress, bad diet, and drinking away the pain had finally caught up to him.

He would eventually leave the hospital, quit drinking and work on eating healthier. He had some good days and some bad days, as did we all. But no matter what changes he instituted now, it couldn’t reverse the damage he had done. One year later, he called me at work and told tests came back from his doctor. They had found a cancerous tumor in his liver, a not-uncommon byproduct of his liver disease.

“Listen, try not to let this ruin your day,” he said with all the bravery he could muster.

“Not sure that’s possible,” I responded.

“I’ve got a follow-up with the doctor next week. I’ll let you know what he says.”

“Okay. Let me know if you need a ride and I’ll come down,” I told him.

“I will. Thanks.”

“I love you, dad.”

“I love you too, son.”

I gently placed the phone down and right there, in the middle of my office, surrounded by unfinished projects, to-do lists, and stacks of papers, I broke down and cried.

I spent the next few months driving back and forth from New Hampshire to Boston, Massachusetts. My kids had sporting events and music recitals. I made every one of them. My father had tests and procedures, and I made those, too. My life became stretched paper-thin. I had to transition between being a dad and caring for my dad. It was tough, but I did it because that’s what you do for your family. We spent many hours laughing and crying together. Other times we simply sat in that sterile, white room, listening to the beeps and hum of the machines, because sometimes there are just no words that can be said.

He never lost his sense of humor, but I couldn’t tell if that was for our benefit or for his. He flirted with the nurses, teased the doctors, and cracked jokes with the cleaning staff. By the time he left, he knew everyone’s name and everyone knew his. But every once in a while, he would slip up and let his pain show through. One day while sitting beside him, I felt him reach over and grab my hand.

“I’m not ready to go,” he said, his voice cracking as tears welled up in his eyes. This was the only time I can ever remember seeing my father cry. He squeezed my hand hard. I squeezed back as if to say, “I’m not ready, either.” Instead, I said, “I know. Everything’s going to be okay.”

My father has been gone for two years, yet I still feel as if he continues to teach me about life even after his death. He made many mistakes when he was alive but I never doubted for one second that he loved me.

In those last few months, days, and hours with him, I found myself constantly going back-and-forth between seeing the world as a father and seeing the world as a son. I couldn’t help but picture myself in his place with one of my children sitting in mine. I kept asking myself how I might be feeling and what I might thinking about if I were him. How would I want my own child to deal with my death? What would I hope to hear them say to me?

In those last few months, days, and hours with him, I found myself constantly going back-and-forth between seeing the world as a father and seeing the world as a son. I couldn’t help but picture myself in his place with one of my children sitting in mine. I kept asking myself how I might be feeling and what I might thinking about if I were him. How would I want my own child to deal with my death? What would I hope to hear them say to me?

What I realized in those moments was that I no longer needed my father to tell me everything was going to be alright. I no longer needed him to be strong for me, to support me, or to reassure me that I could get through this. Instead, I needed to do those things for him. It was as if we had suddenly switched roles and he was the one looking to me for strength and support. And no matter how much I wanted to curl up into a ball and cry, I had to be strong for him. And in doing so, I also showed myself exactly how strong I could be.

At some point, all children grow up. As parents, we only have a small window of time to raise them into adulthood before we send them off into the world. But even though I have been on my own for many years, there was still this subconscious safety net, supporting me and making me feel safe just knowing my parents would be there if I ever needed them. I didn’t even realize it existed until it was gone. For the first time in my life I had to deal with the realization that, if I needed him, my father wouldn’t be there. It may sound strange that at 45 years old, I still felt like I might need my father to help me with something. But in truth, no matter how old I was, I would always be his son.

I miss my father every day. Each time I look at my children and think about how lucky I am to be their father, I also think about how lucky I was to be his son. When I see them smile, hear them laugh, or watch them do something surprising, I can’t help but picture my father watching me do those same things when I was that age, and I imagine him feeling the same pride and happiness that I feel. And that makes me realize he is still a part of my life. Because even though I can’t see or hear him, as long as I continue to be the best father I can be to my children, he will live on in me.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]